Navigation

The art of navigation was one of the most important skills required on board a Tudor ship. Without someone who could use the instruments and read maps the ship could be lost for week on end, and end up miles from its final destination. The ship's navigator was called the Pilot, and by working out how far North or South, and how far East and West his ship had travelled he could accurately position the ship.

The North-South measurement is called Latitude, and is measured in degrees, starting at the equator and working North and South towards the poles. The East-West measurement is called Longitude, and is also measured in degrees, though in Tudor times starting at the home port. There were a number of instruments available to the Tudor pilot to work out latitude with some accuracy, but as yet no reliable way of determining longitude had been discovered, forcing the pilot to use dead reckoning, using information about the ship's speed and direction to work out how far it had travelled.

The North-South measurement is called Latitude, and is measured in degrees, starting at the equator and working North and South towards the poles. The East-West measurement is called Longitude, and is also measured in degrees, though in Tudor times starting at the home port. There were a number of instruments available to the Tudor pilot to work out latitude with some accuracy, but as yet no reliable way of determining longitude had been discovered, forcing the pilot to use dead reckoning, using information about the ship's speed and direction to work out how far it had travelled.

Maps

Maps were an essential part of the Tudor pilot's equipment, they enabled him to find his way to distant parts of the world, to find safe places to anchor and to keep track of his ship's progress across the seas. The maps which Tudor sailors had to use were far from reliable, and often badly drawn. Much of the world was unexplored, and these unknown areas were frequently filled in with educated guesses made by the map-makers, called Cartographers. Cartographers rarely visited the area of which they drew maps and had to rely on information brought back by sea captains. English sea captains were often unable to explore areas owned by the Spanish, so English maps of places such as the Caribbean were often copied from stolen Spanish charts.

Coastal maps of Europe were usually much more accurate, people had been exploring them for centuries, and skilled surveyors were able to map them well from dry land. These high quality maps often had nautical features such as underwater sand banks and depth markings included to provide more information about safe routes into harbours.

Coastal maps of Europe were usually much more accurate, people had been exploring them for centuries, and skilled surveyors were able to map them well from dry land. These high quality maps often had nautical features such as underwater sand banks and depth markings included to provide more information about safe routes into harbours.

Most maps had a compass drawn on to give an idea as to direction, and if any depicted an area over or around a particular line of latitude this was often drawn on as well.

Do you know:

- What areas of the world could not have been mapped accurately by Tudor cartographers?

- What kind of features would a Tudor sea captain have found useful on a map?

Astrolabe

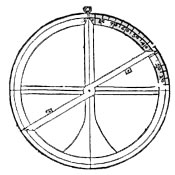

The astrolabe is one of the oldest navigation tools known, and as well as navigation could also be used for astronomy and astrology. The mariner's astrolabe consisted of a flat disc, made of metal or wood with a scale of degrees around the outer edge, and a pointer, known as an alidade which stretched right across the face of the astrolabe and was pivoted in the middle. Mounted at either end of the alidade were plates of brass with small holes in the middle.

The astrolabe is one of the oldest navigation tools known, and as well as navigation could also be used for astronomy and astrology. The mariner's astrolabe consisted of a flat disc, made of metal or wood with a scale of degrees around the outer edge, and a pointer, known as an alidade which stretched right across the face of the astrolabe and was pivoted in the middle. Mounted at either end of the alidade were plates of brass with small holes in the middle.

To work out a ship's latitude the astrolabe was held up a noon by a piece of cord through a hole in the top, and the alidade was turned until the sun shone through the holes at either end. The pilot made a note of where the alidade rested on the scale of degrees around the outer edge, and then used this information to work out his latitude from a table in a book.

Do you know:

- Some astrolabes only had the scale of degrees marked onto the top half, why do you think this was?

- Pilots often had to look along the alidade at the sun, what kind of problems might this cause?

Cross Staff

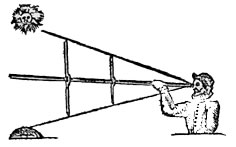

Like the astrolabe, the cross-staff was used by the pilot to work out latitude by first working out the height of the sun. The cross staff was made of a square length of wood, around 1 metre long and marked down one side with degrees, and a sliding wooden cross piece. It was a simple piece of equipment, but was very accurate in skilled hands and was extremely popular in Tudor times.

At noon the pilot would hold one end of the cross-staff next to his eye with the cross piece positioned vertically. He would then slide the cross piece up or down the staff until the bottom edge was lined up against the horizon (where the sea meets the sky) and the top edge was lined up with the bottom of the sun. Then, having made a note of where on the scale of degrees the cross piece lay the pilot would use this information to work out his latitude from the same table used for the astrolabe. With a different scale the cross-staff could also be used to work out the distance between a ship and a stretch of coastline or an island. It could also be used by engineers, builders, surveyors and cartographers (map-makers).

At noon the pilot would hold one end of the cross-staff next to his eye with the cross piece positioned vertically. He would then slide the cross piece up or down the staff until the bottom edge was lined up against the horizon (where the sea meets the sky) and the top edge was lined up with the bottom of the sun. Then, having made a note of where on the scale of degrees the cross piece lay the pilot would use this information to work out his latitude from the same table used for the astrolabe. With a different scale the cross-staff could also be used to work out the distance between a ship and a stretch of coastline or an island. It could also be used by engineers, builders, surveyors and cartographers (map-makers).

Do you know:

- Because a ship was constantly moving a cross-staff could be difficult to use at sea, can you think why?

- Can you think what kind of injuries a pilot might get from using a cross-staff?

Compass

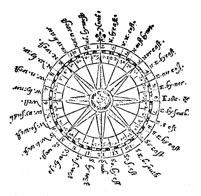

The compass was probably the most important tool for the pilot, as it enabled him to know which direction his ship was travelling in. A Tudor ship would probably have four compasses on board, one for the man steering the ship (helmsman), one on the deck for the officers to use, one for the pilot, and one spare.

A modern compass consists of a flat disc, divided into 360 degrees, over which a magnetised needle sits on a pin and always points North. A Tudor compass was slightly different, it was made with the flat disc attached to the needle so that the whole thing always pointed North.  Rather than being divided into 360 degrees it was divided into points at distances of 11¼ degrees, reached by continuously dividing a circle in half. Each of these points had a name, North, North-west, North-north-west, North-by-North-north-west etc. All young men who wished to become ship's officers would be expected to be able to recite the names of all thirty two points in order, this was known as boxing the compass.

Rather than being divided into 360 degrees it was divided into points at distances of 11¼ degrees, reached by continuously dividing a circle in half. Each of these points had a name, North, North-west, North-north-west, North-by-North-north-west etc. All young men who wished to become ship's officers would be expected to be able to recite the names of all thirty two points in order, this was known as boxing the compass.

By comparing the direction he was travelling in, according to his compass, to the compass drawn on a map a pilot could accurately plot his ship's direction from port to port. If his ship was blown off course and he could work out his ship's new position a compass would be essential to get back on course.Finally, if a ship was travelling along a coast he could compare the directions of two different land marks (often churches) to determine how far away from the coast he was, and to give him an accurate position.

Do you know:

- Why do you think so many compasses were kept on board a Tudor ship?

Log Line

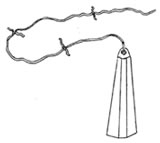

It was very important for a Tudor pilot to know how fast his ship was travelling, and this was done using a tool called a log-line. A log line was a long piece of rope, wound round a spool and with a triangular piece of wood attached to the loose end. At regular intervals along the rope knots were tied. The log-line was used in conjunction with a one minute time glass, or with a phrase or rhyme which took one minute to recite.

To work out the speed of his ship the pilot would throw the end of the log line into the water at the same time as turning his time glass over, or beginning his rhyme. As the rope fed off the spool he would count the number of knots which passed though his fingers in one minute, this would tell him what his speed was in knots, a measurement of speed still used at sea today.

The log-line was not the only method used to calculate speed in Tudor times, but it was probably the most reliable. One other popular method was much simpler. If the pilot knew exactly how long his ship was he could throw something visible, like a scrap of white cloth, off the front (bow) of his ship and count how many seconds it took to reach the back (stern) of his ship. If he knew his ship was 200 feet long, and the cloth took 10 seconds to travel the length of his ship he would know he was travelling at 20 feet per second.

Do you know:

- Which of these two methods would the pilot have used at night?

- Why was it important for a pilot to know how fast his ship was travelling?

Sand Glass and Bell

It was important on Tudor ships to keep track of time, in order to work out how far a ship had travelled and how long sailors had been on duty. Because Tudor clocks were frequently not accurate and were made less accurate by the constant movement of the ship, Tudor sailors relied instead on a sand-glass. A Tudor sand-glass looked very much like a modern egg timer, but instead of running for three minutes, took thirty minutes. Each ship would usually carry two sand-glasses, one in the cabin with the helmsman, who steered the ship, and one on the deck.

The sand glass on the deck was usually next to a bell, and the ship's boy (called a Grommet) was responsible for turning the glass over, and ringing the bell at the same time, so that the helmsman could make sure he turned his glass at exactly the same moment. The ringing of the bell also helped the sailors on the decks and in the rigging to keep track of time. The first time the grommet rang the bell after noon, he would ring it once, the next time twice and so on, until at four o'clock he rang it eight times, then he would start back at one again. The rest of the crew were on duty for four hours, so when they heard the bell ring eight times they knew it was time to change the watch (the men on duty). The 4 o'clock - 8 o'clock part of the day was divided between two watches, working two hours each, in order to make sure that sailors did not have to be on duty at the same time each day The ringing of the bell also helped the pilot to keep track of the ship's movement and make sure that the ship turned at the right time. If the ship was trying to sail against the wind it would move from one direction to another at regular intervals, this is called tacking. If a ship was tacking the helmsman would often change direction every half hour, and he would keep track of this by the ringing of the bell.

The sand glass on the deck was usually next to a bell, and the ship's boy (called a Grommet) was responsible for turning the glass over, and ringing the bell at the same time, so that the helmsman could make sure he turned his glass at exactly the same moment. The ringing of the bell also helped the sailors on the decks and in the rigging to keep track of time. The first time the grommet rang the bell after noon, he would ring it once, the next time twice and so on, until at four o'clock he rang it eight times, then he would start back at one again. The rest of the crew were on duty for four hours, so when they heard the bell ring eight times they knew it was time to change the watch (the men on duty). The 4 o'clock - 8 o'clock part of the day was divided between two watches, working two hours each, in order to make sure that sailors did not have to be on duty at the same time each day The ringing of the bell also helped the pilot to keep track of the ship's movement and make sure that the ship turned at the right time. If the ship was trying to sail against the wind it would move from one direction to another at regular intervals, this is called tacking. If a ship was tacking the helmsman would often change direction every half hour, and he would keep track of this by the ringing of the bell.

Do you know:

- If a Tudor ship's crew was divided into four "watches" and each watch was on duty for four hours at a time, how many times each day would a watch have to go on duty?

Traverse Board

If a Tudor pilot wanted to work out his longitude (how far East or West he had travelled) he needed to keep an accurate record of which direction his ship had been sailing in and how fast she had travelled during a set period of time. The pilot was often too busy to keep this record himself, so it was usually the job of the helmsman. Many of the common sailors in Tudor times were unable to read or write properly, so instead they used a Traverse Board to keep the record of the ship's movements.

A traverse board was a flat piece of wood, often shaped and decorated, but sometimes just a plain rectangular shape. On the traverse board was painted a picture of a compass, and a table to show speed. There were eight circles of holes drilled in the compass face with a hole in each point of the compass, and the speed table also had holes drilled in it.

A traverse board was a flat piece of wood, often shaped and decorated, but sometimes just a plain rectangular shape. On the traverse board was painted a picture of a compass, and a table to show speed. There were eight circles of holes drilled in the compass face with a hole in each point of the compass, and the speed table also had holes drilled in it.

Each time the helmsman heard the bell ring and turned his sand-glass he would put a small wooden peg in one of the holes in the compass, corresponding to the direction the ship had been travelling, and one in the speed table, to show the speed. At the first bell he would put a peg in the innermost circle of holes, and in the first row of the speed table. At the second bell he would put a peg in the second innermost circle and the second row on the speed table. He continued this until the end of his four hour duty, when all eight circles would have a peg in

When the bell rang eight times the pilot would examine the traverse board and be able to tell at a glance where the ship had travelled in the last four hours. He would make a note of this in the ship's record, called a log book and would mark his new position on a map.

Do you know:

- Why were there eight sets of holes in the traverse board?

- How many Traverse boards do you think each ship needed to carry?

Sounding Lead

When a ship enters a harbour it is important that the pilot knows how deep the water is below, to make sure the ship does not hit the sea bed. Today this is done by sonar, an electronic system, but in Tudor times the pilot needed to use a sounding lead. A sounding lead was a simple device, consisting of a lead weight, with a rope attached to it. At regular intervals down the rope, usually every fathom (six feet, or a little under two metres) a knot was tied, at every fifth knot a small piece of leather was tied into the knot, and at every tenth knot two pieces of leather.

When a ship enters a harbour it is important that the pilot knows how deep the water is below, to make sure the ship does not hit the sea bed. Today this is done by sonar, an electronic system, but in Tudor times the pilot needed to use a sounding lead. A sounding lead was a simple device, consisting of a lead weight, with a rope attached to it. At regular intervals down the rope, usually every fathom (six feet, or a little under two metres) a knot was tied, at every fifth knot a small piece of leather was tied into the knot, and at every tenth knot two pieces of leather.

As the ship sailed into harbour a sailor would throw the sounding lead as far forward as he could, and when the ship came up to where the lead had landed he would count the knots and call out the depth of the water to the pilot, this is called heaving the lead. Sometimes the lead weight on the end of the line had a small hole drilled into the bottom, and this hole was filled with animal fat called tallow. When the lead line reached the sea-bed some soil would get stuck to the tallow, and since different harbours have different kinds of soil, the pilot could use this to help work out his location.

Do you know:

- Why do you think the leather was tied into every fifth and tenth knot?